New Brunswick’s approach to natural gas is full of cracks

There are a number of concerns regarding the development of natural gas in New Brunswick. The Province has no long term energy plan, a poor royalty structure, and citizens have a real lack of confidence in our government to protect their property rights. As well, there is a poor understanding of the economics of natural gas industry and a lack of respect for the environment. This report, although brief, may improve the understanding of the issues.

A long term energy policy.

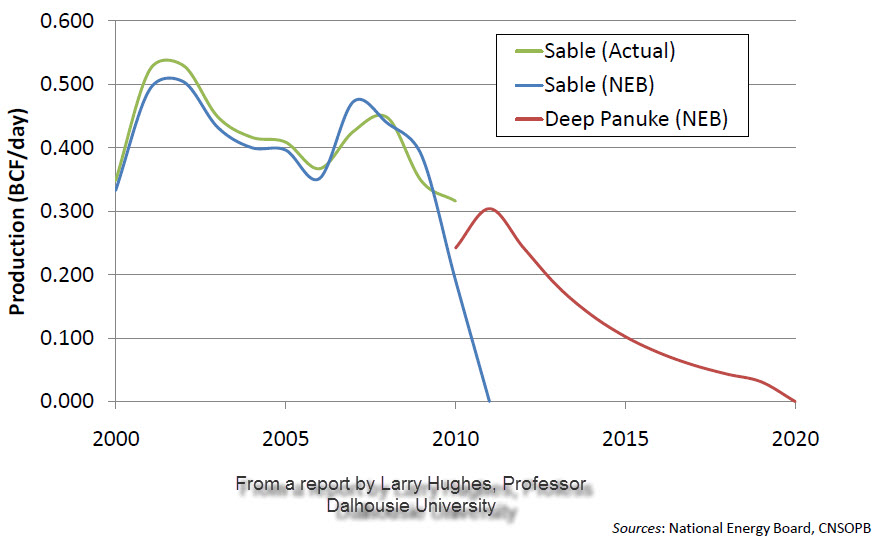

Our NG supply is presently coming from Sable Island. By roughly 2017, it will be nearing depletion and unable to supply New Brunswick. Western Canada gas is not connected to Atlantic Canada by pipeline. One alternative is the use of LNG arriving from countries like Algeria and Qatar, which introduces questions about security of supply and prices in coming decades. Our world will increasingly be defined by energy shortages, energy nationalism, resource wars, and competition for those dwindling supplies. It is possible that we might import from the US, itself a large user of natural gas. Note that 3% of Canada’s natural gas production is from Atlantic Canada and only a very small percentage of that is from New Brunswick – Corridor Resources. As the conventional natural gas supplies in NB and NS play out, the size of unconventional reserves (shale gas) is still unclear. Recent wells by Apache (a partner of Corridor), who drilled horizontally into the shale level, were unsuccessful.

Our NG supply is presently coming from Sable Island. By roughly 2017, it will be nearing depletion and unable to supply New Brunswick. Western Canada gas is not connected to Atlantic Canada by pipeline. One alternative is the use of LNG arriving from countries like Algeria and Qatar, which introduces questions about security of supply and prices in coming decades. Our world will increasingly be defined by energy shortages, energy nationalism, resource wars, and competition for those dwindling supplies. It is possible that we might import from the US, itself a large user of natural gas. Note that 3% of Canada’s natural gas production is from Atlantic Canada and only a very small percentage of that is from New Brunswick – Corridor Resources. As the conventional natural gas supplies in NB and NS play out, the size of unconventional reserves (shale gas) is still unclear. Recent wells by Apache (a partner of Corridor), who drilled horizontally into the shale level, were unsuccessful.

The recent provincial Energy commission report suggests expanding the use of natural gas within the province, but makes no mention of restricting usage or export levels of New Brunswick gas to ensure adequate supply for our children and grandchildren. We have no solid evidence of a viable in-province supply at this time. There is plenty of hype surrounding the expectations of shale gas resources in North America.

The existing royalty structure

New Brunswick has little rational incentive to exploit its natural gas given the return on energy supplies. Any businessman would be reluctant to rent a property for 5% of its value, let alone sell off a non-renewable energy resource of strategic value in the future.

Our present royalty is 10% of the wellhead price. Given the subsequent deduction of costs, we see in 2010, a recovery of 2% of the revenue of the production from Corridor. The current glut on the Boston market and the structure of the royalty ensure that we receive a minimal return.

Public confidence in the government of New Brunswick.

The extensive development of natural gas proposed requires the consent of the people of New Brunswick. The experience of about 60 families in the Penobsquis area with water problems and subsidence cracking basements and creating sinkholes in fields has caused a confidence gap between citizens and their government. Based on government responses to the problems caused by the Potash mine, we can predict that anyone having water quality issues related to hydrofracking will be “on their own” in regards to seeking justice.

The government of New Brunswick has refused to release the data related to subsidence gathered by a consultant required as part of the mining process so that the families can defend their rights before the mining commissioner. Will the same approach apply to water testing by shale gas companies? How is it possible that we allow the socialization of the environmental problems of industrial activity to innocent citizens while the Potash Corp made $1.8 billion of profits in 2010?

The economics of natural gas.

Horizontal drilling and fracturing are necessary to get gas out of the shale rock and this costs more than conventional vertical drilling. A shale gas well’s production will decline at significant rates of 65% per year or more, which means that constant drilling is necessary to maintain production levels. Although the cost of a well in Arkansas may be as low as $3 Million, the Apache wells in Elgin cost about $12 million each. The breakeven point for shale gas may vary from $5 to $8 /mmbtu.

The initial rush of drilling in the US has driven market prices for natural gas down to $4 per mmbtu or less. This is below the cost of production leading to less drilling taking place now. It is now 20% of US production, which has reduced the export volume and prices of Canadian natural gas sent to US markets.

The Energy Report by Thompson / Volpe suggests that natural gas prices will remain stable in New Brunswick for the next ten years. This seems unlikely given that availability of gas is dependent on companies actually making a profit. It is more likely that as depletion takes effect, oil prices rise and natural gas displaces some functions of oil, then NG prices will again rise.

The problem remains that New Brunswick is poorly positioned to compete against shale gas originating in the US. One can see from the chart of prices, that although volatile, the price has rarely stayed over $8 / mmbtu for significant periods. The cost of transport to market is about $1.40 per mmbtu or 20% of the market price. Our prediction – Natural gas will remain a boom and bust industry with hardship for companies drilling in New Brunswick. We might consider a different economic model for this industry.

The distribution of natural gas -Enbridge

Starting a new distribution network is an expensive business and building a customer base requires time. Enbridge expected to lose some money in the initial years. However, the conversion rate of customers has been slower than anticipated. So far, Enbridge has lost about $170 million which would be paid back once they start to make money. To attract customers, they have offered between 10 and 20% savings over oil and electric rates. When oil prices went up, so did the delivery charge and this has caused some concern among the industrial customers, like Flakeboard. The very large industrials get a bypass license so they get the very best price. The government is presently renegotiating the terms of the 20 year agreement which ends in 2020.

Fracking, a questionable practice

Fracking is a complex process. Without fracking, shale will not release natural gas. To get large volumes of gas, many wells would need to be drilled each year. How often does fracking result in cross – contamination of the water supply? We know the answer is not zero. Is it 1%, or is it 10%. Is there an acceptable level of failure? The people who are affected would say no. They take the risks with no compensation or protection. We are drilling without acceptable standards, and without adequate inspection. Will the prior water testing be in the public domain?

Conclusions:

Our present approach to natural gas fails on many levels. One senses the desire to export at any cost and with limited economic return. We are at the end of the fossil fuel era, clearly evident by the costly development of a low quality resource – shale gas. We are left with many questions and decisions to be made. We need a moratorium on drilling to have time to answer many of these questions.

- What is the level of industrialization of the province that we are prepared to accept?

- How can we protect those citizens affected (Penobsquis) and rebuild the confidence of the people?

- Can we improve the royalty structure or should we have a totally different model.

- Should we use natural gas to produce electricity given its lower efficiency rating? Should we consider gas New Brunswick’s ‘transition’ fuel easing the difficult switch to renewable energy sources?

- Should we export the resource, or use it in-province over a century? Do we want the responsibility for US energy supplies as fossil fuel cost skyrocket?

- What are the standards, the inspections, the water quality testing and the insurance that provides the best protection possible?

- Might leaving shale gas underground be the best gift we could leave for our grandchildren?